Photo from Shalom Seri & Naftali Ben-David (Eds.) A Journey to Yemen and its Jews. 1991. Tel Aviv.

It tends to be asserted – and has been for decades – generally by those who oppose Israel, that Jews who lived in Arab lands were just fine – that there were no problems between Arabs and Jews before the State of Israel was established. This assertion is made with absolutely no knowledge of the facts! The message intended to be conveyed is that it is the fact of Israel’s establishment and existence that is the source of all problems between Arabs or Muslims and Jews in the Middle East.

Having researched on the situation of Jews in Yemen during the period preceding their main exodus to Israel in the 1950s “on the wings of eagles”, I am in a position to respond to such assertions with particular reference to Yemen. So I’ll provide a brief account of the situation of Jews in Yemen, mainly from the time of the second Ottoman occupation of that country in 1872 which lasted until 1918, after which time it came under the rule of Zaydi imams.

The Arab population of Yemen was divided between a number of Muslim sects. The ruling sect was the Zaydi (Shi’ite) sect. Judaism was the only other religion to have survived in Yemen apart from Islam.

Rank

Jews came at the bottom of the hierarchical system in Yemen. This system was caste-like in respect of there being a traditional connection between rank and occupation, and prohibitions of various degrees existing against intermarriage and the sharing of meals between members of different ranks. In order of descent, the ranking system was as follows:

I Royal lineage and some other Zaydi lineages.

II Sayyids – holy men, who claimed descent from Husayn and Fatima, the daughter of Mohammed.

III Mashayikh – large landowners and religious scholars. (Bujra 1971)

The above three ranks were accorded prestige and authority. Further down along the scale were:

IV Gabili – small landowners and free farmers.

V Merchants

VI Pedlars, vagrants, slaves and other pariah groups

VII Ahl-Al-Dhimmi – protected peoples who, in Yemen, were the Jews.

It seems that in rural areas, category VI (above) was actually considered, and treated as ranking, lower than the Jews – at least among the tribespeople.

Although the Jews had no choice but to tolerate the place allocated to them in Yemenite society, I find no evidence that they accepted that they were inferior to anyone because of their rank. It is interesting to note that they referred to the class of Muslim holy men as “impures” (teme’im), (or “Jew baiters”,) expressing contempt.

Anti-Jewish legislation

During the first century of the spread of Islam, Muslims were a minority in the countries they conquered, and had to depend on the conquered peoples for their military security, administration, food, and finance. However, during the second and third centuries of the Islamic era, Muslims became the majority in all the conquered countries. At this time, they developed an elaborate religious law, and began to pass anti-Jewish and anti-Christian legislation, some of which was taken directly from Byzantine anti-Jewish legislation, and which continued to apply in Yemen up to the time when the majority of the Yemenite Jews were flown to Israel in “Operation Magic Carpet” in 1949 and 1950.

The status of the Jews in Yemen was governed by two sets of laws: those deriving from the Covenant of Omar, and those specific to Zaydi legislation in Yemen. The Covenant of Omar, originally attributed to the second caliph, Umar ibn Khattab (d. 644), is a collection of discriminatory regulations and restrictions applied to the Ahl al Dhimma (people of the covenant) – protected peoples – this status being open to Ahl Ketab (people of the Scriptures) – Christians and Jews. These regulations were issued by various Caliphs and sultans from the early years of the eighth century to the mid 14th century when the Covenant received its finishing touches, whenever religious fanaticism or envy directed towards the protected peoples spilt over. They were intended as interpretations of the following prescription of Mohammed:

Fight those who do not practice the religion of truth from among those to whom the Book has been brought, until they pay the tribute by their hands, and they be reduced low.

Because Jews and Christians are believers in the essential truth: that there is one God, they have a right to be protected together with their property. However, they only have this right so long as they pay jizzyah (poll tax) and comply with a number of other laws. The (unrealisable) idea behind the payment of jizzyah was that while Muslims should be responsible for defence and administration, the infidels should bear the entire fiscal burden of the country and the task of keeping up its economy.

According to the Covenant of Omar:

I Jews could not bear witness against a Muslim, or give testimony in a Muslim court. This in theory deprived Jews of any legal rights, but in Yemen, this severe disadvantage was counterbalanced by the institution of “protected comradeship”, as described below.

II Ahl al Dhimma could not carry arms or ride on horseback, as this would give them an advantage over some Muslims in terms of power or height.

III They had to display a respectful attitude towards Muslims. On passing a Muslim, a Jew had to walk on his left side. They were not permitted to engage in any conduct considered offensive to Muslims, such as blowing the shofar loudly, praying loudly, or displaying the cross in public. (A shofar is a ram’s horn blown on the Jewish New Year and other solemn religious occasions.)

VI They could not build their houses higher than those of Muslims.

V They had to dress differently from Muslims.

VI They could not attain to government posts, since prestige and authority attached to such posts could accrue only to Muslims.

VII Non-Muslim doctors or pharmacists were forbidden to treat Muslims on the grounds that they might poison them, or that through control of a patient’s body, they might also gain control over his soul. (In practice, Jews were appointed doctors, and even viziers, to sultans and imams in many Islamic countries, including Yemen.)

VIII Some law books of Islam state that a non-Muslim may not engage in the same commerce as Muslims. This was reiterated in a public proclamation by the Imam of Yemen in 1905, but its application was limited. The most ancient law books of Islam discriminate against non-Muslims in the economic field by imposing customs duties at 5% on the value of their merchandise, whereas Muslim merchants paid two and a half per cent, and the minimum value of consignment on which duties were paid was 40 dinars for a Muslim, and 20 dinars for a non-Muslim.

IX Non-Muslims were not permitted to use saddles.

X They could not look upon the genitals of a Muslim in the bath house, while separate bath houses were to be built for Jewish women so that they did not bathe together with Muslim women.

XI Non-Muslims, as well as Muslims, were forbidden to lend money for interest.

XII Finally, Jews were not permitted to study the Torah outside the synagogue.

In Yemen, Jews were subjected to the above legislation in varying degrees of intensity, up to the time when they left.

In addition to the Covenant of Omar, regulations specific to Yemen were imposed upon Jews, who were often called upon to carry out tasks thought to contaminate Muslims. Tobi (1999) relates that the introduction of discriminatory laws began in Yemen in the 15th century with a significant change in attitude of the Zaydi government towards Jews. When the Ottomans governed a large part of Central Yemen 1872 to 1919, they tried to raise the status of Jews to a level equivalent to that held by Jews elsewhere in their empire. But their efforts ceased in the face of opposition on the part of sectors of the Yemenite population and religious scholars. However, tribal sheikhs did not strictly enforce these laws. For example, while in San’a (Yemen’s capital) Jewish houses were lower in structure than Muslim houses, there was mostly no difference between their heights in rural districts. In the North and North East of Yemen, Jews, similarly to the local tribesmen, carried arms, and in Northern Yemen, Jews were even taught to use guns by tribesmen.

According to Tobi, the Yemenite governments were among the most extreme of the Islamic countries with regard to their treatment of Jews as anjâs (unclean). In San’a, the decree of the “scrapers” or “dung gatherers” was revived from 1846 until 1950, having previously been imposed on them from 1806 to 1808. This decree stipulated that Jews be forced to clean the sewers in the city. Jews were also obliged to remove camel and horse carcasses as part of the decree, and clear accumulated filth from Muslim streets, and the dead body of a Christian had to be buried by Jews. In practice, a small proportion of Jews were willing to carry out these tasks for a higher than normal remuneration on behalf of the Jewish community, and Nini (1991) relates how this resulted in a type of “caste” of “untouchables” among the Yemenite Jews, this status being passed down within the families, and with other families refraining from marrying from among them. These Jews were not called up in the synagogue to read the Torah, nor invited to festive occasions. Their children were excluded from studying with other children. Under Arab rule, the “dung gatherers” were unpaid for this work, but under the Ottomans, they were paid gold pounds and silver coins, and their economic situation improved. This decree was a strong motivating factor in the migration of San’ian Jews to Palestine from 1881, and the dispersal of Jews throughout Yemen and into Egypt. In 1949, Muslims in San’a prevented the migration of “dung gatherers” to Israel.

Upon the capture of San’a by the Ottoman Ahmad Mukhtar who was well disposed towards the Jews, the “decree of the dung gatherers” and the “orphans’ decree (see below) imposed on Jews were temporarily abrogated. However, this met with strong pressure applied by the Muslim religious dignitaries of San’a to reinstate these decrees. Similarly under pressure exerted by these Muslim religious dignitaries, the jizzyah (poll tax) previously imposed on the Jews of San’a was revived and raised from 27 to 77 riyals per month. Despite the positive intentions of Ahmad Mukhtar and the initial Ottoman administration towards their Jews, according to Nini, illegal taxes and bribes and their arbitrary and forceful extortion, became more prevalent under the Ottomans.

According to Nini, between 1882 and 1900, payment of jizzyah was one of the greatest burdens endured by the San’a community. During the Festival of Succoth 1990, Ottoman troops broke into the Jewish quarter of San’a and arrested ten of the most prominent community leaders, who were the overseers of the jizzyah payment. They were incarcerated and tortured for three months, while the Ottoman administration appealed to the Jewish religious court to make payment. This situation motivated a number of Jews to migrate to Palestine.

Jews under the protection of the Zaydi tribes in North and North East Yemen, where the Ottomans were not in control, were obliged to pay jizzyah to the central authority in San’a and also to pay the tribes under whose protection they were living. A compromise was reached where a symbolic payment was made to the tribal Sheikh.

Another calamitous regulation imposed on the Yemenite Jews by the Ottoman authorities was the “decree of the stretcher-bearers” in 1875. This decree imposed on the San’ian Jewish community the task of carrying wounded soldiers from San’a through Manakha to Hudayda. This was a treacherous journey along narrow winding paths at the edge of precipices, which was dangerous even for an unladen traveller. On the eve of the festival of Succoth, they were ordered to send 80 Jews to carry wounded Ottoman solders. This entailed desecrating the holy festival. Therefore the Jewish community leaders refused to comply with this command unless those commandeered were specifically requested by name.

“On the following day a manhunt was held in the Jewish quarter, and those apprehended were cruelly beaten. Some of them succeeded in bribing the local Muslim soldiers and evading arrest. Those caught were thrown into jail when four were allocated a wounded soldier and the terrible journey to Manākha commenced. The accompanying troops urged the Jews on with whip lashes.” (Nini, 1991, 74)

A number of stretcher-bearers died by the wayside on the treacherous route. They had been forced to desecrate both the Sabbath and a holy festival, which was something unheard of under the Zaydi regime before the Ottoman occupation. Zaydi Imams and local rulers were most careful not to incur such desecration. Any Jews summoned to the Zaydi authorities on the eve of the Sabbath could evoke the Prophet’s protection of the Jewish Sabbath, and delay presenting himself until after the Sabbath.

Another hardship specifically suffered in the 19th century by those Jews who were in charge of minting coins, were accusations of counterfeiting coins. According to Nini, these accusations were almost all groundless.

From the time of their conquest in 1892, the Ottoman Turks forced the Jewish community of San’a to mill grain for their soldiers, failing which Jews and Yemenite Muslims would be beaten by Ottoman soldiers. Jewish women were therefore forced to mill flour for the Ottoman troops, and when this was too strenuous for them, they would be helped by their menfolk. At the turn of the 20th century, after years of drought and famine, many Jews had moved to the villages of Yemen, or to Palestine or Egypt. Thus the Jewish population of San’a diminished considerably, and yet the milling quota imposed on them remained the same. The imposition of this “flour-milling decree” entailed the violation of their holy festival of Passover, as the Jews were unable to keep their milling stones kosher in accordance with the rules of Passover, and led to the migration of many Sa’nian Jews to Palestine.

Another great hardship and violation suffered by the Jews of San’a in the 20th century was perpetrated by Imam Yahya al-Muta Walkil after ascending to power, when he had all the synagogues built in San’a during Turkish rule destroyed.

In accordance with Orthodox Islam, conversion to Islam should not be achieved by force, and according to Nini, there is no mention in Muslim law of a religious injunction to convert to Islam the “People of the Book”. However, in Yemen, in their eagerness to gain proselytes, an edict issued in 1921 and enacted upon with vigour from 1925 dictated the forced conversion of orphans. This decree was in force in the 19th century up until the Ottoman conquests in 1840 – 1872, and 1872-1905, and was then revived in the 1920s under pressure from “fanatical religious dignitaries”. Tobi describes Zaydi-ruled Yemen as unique among the Muslim states in its promulgation of the Orphans’ Law and Dung Collectors Law. (Besides religious zeal, another factor which gave rise to this edict may have been the Imam’s need, from time to time, to fill vacancies in his “orphanages”, which were in fact military academies.) An orphan was defined as one whose father had died before he or she had attained puberty, and was to be converted even if in the meantime he or she had grown up and married. According to Goitein, the legal basis for this is found in a statement attributed to Mohammed, that everyone is born into a natural state of religion – that is, Islam – and that other religions are merely customs taught to a child by his parents. As the mortality rate was very high in Yemen, mothers were often separated in this way from their children, and brothers and sisters separated from each other. Attempts were made to save orphans from such a fate. They would be sent to other villages where they could be passed off as the children of relatives, or anyone who would look after them. Such attempts were not always successful, and it was not uncommon that they were betrayed by their own people. This is the law which Yemenite Jews found most intolerable, and felt most bitter about. In Zaydi tribal areas, however, Nini informs us that conversion was not enforced, and orphans would therefore be sent there for refuge.

There were also other circumstances in which proselytes were made. Jews converted to Islam to escape the consequences of false accusations, and other desperate situations. In times of famine, many Jews (apparently, mostly women) accepted Islam as the only means of obtaining food from the Imam for themselves and their children. An example of this was in 1905 when Imām Yahyā Ibn Muhammad Hamīd al-Din planned a rebellion against the Ottoman rulers. He ordered his followers to lay siege to Ottoman-ruled cities, including San’a, where an estimated 6000 Jews starved to death: 80% of the Jewish population of San’a. Mass conversions to Islam occurred at this time among the Jewish population, as the Muslim clergy cared for converts.

The right to leave Yemen was denied to Jews, for once they left the territory, they forfeited their right to security of their persons and property. The reason for this restriction was perhaps the desire to keep their craft skills in Yemen, or else to inhibit their trading. In particular, the territories of the enemy: Turkey, and those under the British protectorate, were considered out of bounds. In practice, however, there were many Jews who managed to leave Yemen. This was facilitated by the British conquest of Aden in 1839. Many of Aden’s 800 original inhabitants were Jewish, and as a British protectorate, the city became a flourishing port, attracting Jews from other parts of Yemen. From here, they were able to migrate to other countries. Nini states that Jews migrated to Aden, Egypt, Ethiopia, India and Palestine, while Muslims also migrated to neighbouring countries.

The Jews of Yemen lived separately from Muslims, in separate villages, or different quarters in the towns. In San’a, this prohibition originated in the time when its Jews were expelled to the uninhabitable region of Mawza (1679-1680) where their population was decimated. When it was subsequently realised that there were no craftsmen left in San’a, those Jews surviving were allowed to return, but were forced to take up residence outside the city walls, rather than return to their homes. However, in the case of smaller villages where there were only a few Jewish families, Jewish communities did not live separately from the Muslim population.

The interpretation and enforcement of the restrictions and prohibitions imposed on the Jews in Yemen varied from district to district, and from one period to another. For the two centuries preceding the Jews’ departure from Yemen, their majority were mostly located in Zaydi regions. The Northern tribes were independent of the government in San’a, and in their regions, the status of the Jews was in effect determined by the tribal code of honour rather than any restrictive regulations derived indigenously, or from the Covenant of Omar. Eraqi-Klorman (2009) states that tribal law would override Shariah in these regions. Y. Saphir (1886) reported in the second half of the 19th century that in almost all the Jewish communities in central Yemenite plateau, Jews were found who had fled from San’a because of oppression encountered there.

The extent to which the laws were imposed upon Jews depended a great deal on the good-will of their Muslim neighbours. Habshush, the San’ian Jew who narrates Travels in Yemen (Goitein,1941), informs us, for example, that the Jews in al-Madid were relatively well-off since the Nihm tribesmen were “good-natured”, and it did not matter to them if a Jew raised his voice or built his house too high. In this part of Arabia, he continues, the tribal code of honour alone counted, even to the exclusion of the law of Mohammed. According to the former, “the overlord is judged according to his protégés”. Therefore, the welfare of the Jews of Nihm was an indication of the quality of the tribe of Nihm itself.

This point on Jews’ welfare depending on the goodwill of their neighbours is also borne out by Tobi. For example, despite the restrictions stipulated in the Covenant of Omar against Jews’ bearing arms, and this not being “customary” in Yemen – (although it was Jews who manufactured weapons) – he states that Jews in northern Yemen were not bound by this restriction and went about armed and unfearful. In fact, they identified with the tribes among whom they lived, and supported and co-operated with the Imams in their revolts against the Ottoman occupiers, sometimes joining the forces against them. (In this way, they contrasted with the Jews of central and Southern Yemen, where it appears they favoured the Ottoman and the British rulers, according to Tobi, in the case of the Ottomans, presumably before their rule became oppressive. When the Ottomans conquered Yemen in 1872, “The Jews greeted the event as a miracle”. [Nini, 1991] This joy was particularly held by the Jews of San’a who lacked tribal protection, and were vulnerable to tribal attacks. They thought that the Ottoman presence would protect them from the sieges and starvation these onslaughts incurred.)

According to Tobi, there is a great deal of evidence that in central and Southern Yemen, the prohibition against riding on horseback was enforced. Only a sick Jew was allowed to ride a donkey, and then was required to yell: “’ala ra’yah” (“By your leave!”) in order to placate any passing Muslim. In San’a, in 1936, Muslims were allowed to haul Jews off their donkeys. In N.E Yemen, by contrast, riding was permitted to Jews even on horseback.

In Central Yemen, Jews wore black only in obedience to a government decree against fine clothing, and for fear of arousing envy among Muslims. In 1667, the Decree of the Headgear was implemented, forbidding Jews to wear elaborate turbans . However, in North Yemen, Jews are depicted in colourful and resplendent clothes and turbans.

Following “messianic activity” in 1667, Jews were ordered to grow sidelocks – which was not in force in Northern Yemen.

In accordance with the Covenant of Omar, Jews were forbidden to build houses higher than those of Muslims. While this was the case in San’a, and perhaps in other cities and large towns, again, in Northern Yemen, this stipulation was not enforced, and Eraqi-Klorman states that there was mostly no difference in height between Muslim and Jewish dwellings in rural areas. Tobi relates that in Sa’dah and Haydan, there were some grand Jewish houses 5 or 6 storeys high, with some 15-20 rooms. In the district of Barat, Jews and Muslims did not live in separate quarters.

Other stipulations specific to Yemen or deriving from the Covenant of Omar – relating to the “uncleanness” of Jews in the eyes of Zaydis, a Jew’s obligation to pass a Muslim on his left side, and the disqualification of a Jew’s testimony, were not in force in Northern Yemen.

The majority of Jews depended for their wellbeing on an institution called “protected comradeship”, whereby a Jew, or a whole village of Jews, submitted themselves by a solemn ritual of sacrifice to the protection of a powerful tribe (or even several) – in particular its Sheikh – for whom it was a matter of the highest honour to administer justice. (Subordinate Muslim groups such as the Qarawi, also acquired tribal protection in the same way.) A tribal chief was obliged to accept a request for tribal protection, otherwise his reputation would be at stake. Eraqi-Klorman states that the obligation of a tribe to protect a jar (protected subject), and the shame of any failure to do so, was related to viewing the Jews as a weak group within the tribe, and to “perceiving their men as having a blurred gender identity, as not being real men”.

The following account (Goiten, 1947) indicates the efficacy of the institution of “protected comradeship”. Joseph Shukr, a Jewish protected comrade of Bait Luhum – the most powerful tribe in the district – was repairing a leather bucket at a farmer’s house, when a “half-witted” Muslim approached him and, before Joseph realised his intention, struck him on the head with a piece of wood so violently that he died immediately. Afterwards, the murderer asserted that the Jew had bewitched him into murdering him. The news of the murder spread quickly throughout the whole village and to nearby hamlets, until, that evening, 2,000 farmers of the Bait Luhum tribe had armed themselves while a similar number had made their way to Ibn Mesar, the advocate for the murderer, also prepared for battle. Eventually, the noblest sheikhs of the four greatest tribes of Yemen were called upon to judge the matter, and decided that since the murderer was not in full possession of his faculties, he was not really responsible for his crime, which could not therefore be avenged with blood. Instead, his advocate was ordered to pay quadruple blood money: twice for the family of the murdered Jewish man, and twice for the protector, and in addition, he had to meet the very high legal costs. This judgement was accepted and fulfilled by Ibn Mesar, and the murder was thus considered avenged. This was essential to the Muslims, for if the crime had remained unavenged, the murdered Jew would “ride on the murderer” at the last judgement.

Muslims can forgive one another, but Allah himself takes care of the unprotected Jew’s revenge. (Goitein, 1947)

Therefore, while Jews may have been considered as “weak”, we can see that fear was a factor in their protection: that they were feared – particularly in the hereafter.

The Jews’ observance of their religion was a matter of concern to tribesmen in Yemen. Muslims were dependent for their well-being on Jews’ observance of their religious laws, and therefore felt threatened by Jews who flouted any of these laws that they were aware of – the main one being the commandment which is the most important for Jews: observance of the Sabbath. For example, Klorman recounts an incident in which a Jewish man, Shar’abi, returned late after business dealings, and arrived home only barely in time for the Sabbath. The village sheikh, ‘Ali Qa’id, shouted at him angrily for being late, and for having insufficient time to prepare for the Sabbath, which he was therefore in danger of desecrating. It seems that the concern of the tribesmen was that any irreligiosity would adversely affect the whole community, including Muslims. Therefore they saw the Jews’ compliance with their own laws as a responsibility they bore on behalf of everyone.

Jews would be called upon to hold prayers for rain at times of drought, being believed to have control over the climate. But its corollary also applied: Jews were believed to have the power to disrupt the climate and halt rainfall.

Some Jews were renowned for specialized magic skills, such as the power to control demons and exorcise them from people who had become possessed by them. However, with this dependency and belief in Jews’ power came fear that Jews could use such power for harmful purposes. Klorman mentions sources relating to Jews intentionally performing sorcery, and to Jews whose actions were incorrectly interpreted as sorcery, and who were therefore “punished”. Klorman describes the case of Ba’al Hefetz (literally: “Owner of the book” – a title attributed to a mori with kabbalistic knowledge of the Book of Zohar) Busi Shalom from the village of Hamd Sulayman in the Shar’ Ab district, at the beginning of the 20th century. The area’s tribesmen:

“…sensed that something was wrong about this Jew. They suspected that he was causing trouble with their women, and that he instigated wives to dislike their husbands and created hatred between them. Therefore they ambushed him on the road, caught him, and tied him in a sack and threw him into a reservoir.” (Klorman 2009:129)

Therefore beliefs were held by Muslim tribesmen in a Ba’al Hefetz’s ability to control other people’s minds.

The respect and dependency of Muslims on the religious observance of Jews, and on mystical powers attributed to them, which placed upon Muslim tribesmen the imperative to protect Jews and their religious observance, could and sometimes did, it seems, turn to fear of their relationship with mystical sources, which could become dangerous and fatal for Jews who found themselves as the target of such fear.

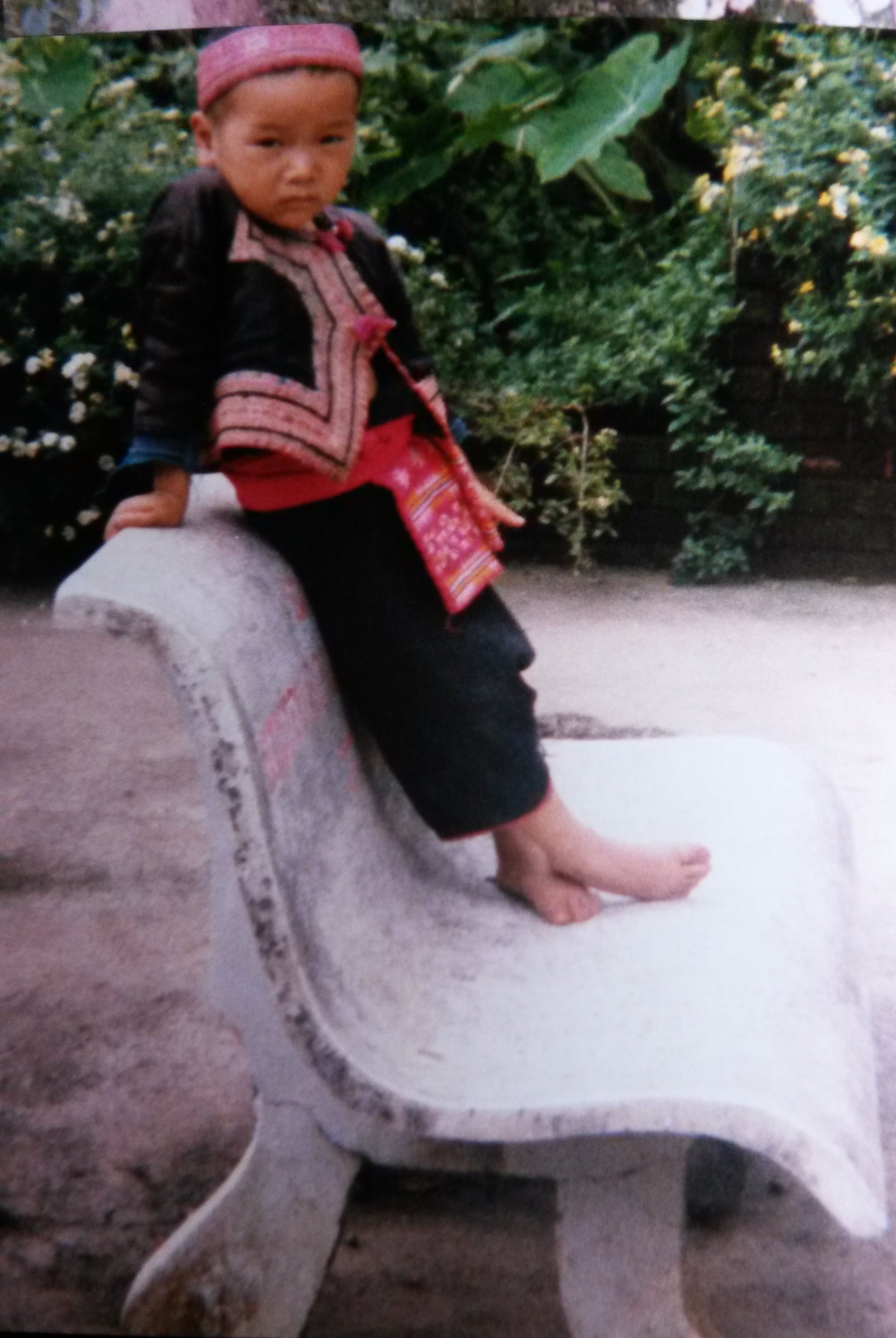

Woman in rustic dress. Photo from Daughter of Yemen, edited by Shalom Seri

Economic Situation

The Jews of Yemen were scattered throughout the whole of Yemen in more than 1,000 localities: villages, towns, and some cities. 85% of Yemenite Jews lived in rural or tribal areas in order to be near their clients who were generally farmers.

By law, Jews could not engage in the same occupations as Muslims who, in Yemen, were predominantly agricultural. Nevertheless, Barer (1952) was told by Yemenite Jews that about half of their numbers were farmers: that Jewish villagers frequently had their own fields, wells, fruit trees and olive groves. However, they were not permitted to be freeholders, but had to lease their land from Muslims. In San’a and the seaports, some Jews were merchants, dealing especially in coffee. Primarily, the Jews filled an occupational niche in Yemen as craftsmen, whose skills were passed down from father to son. As the country’s craftspeople, the Muslim population was dependent on their skills.

Nevertheless, the Jews were far more dependent economically on the Muslims than vice versa, for in the considerable times of famine and drought, the Muslims could temporarily dispense with the products of the Jews, whereas the Jews could not do without the agricultural produce of the Muslims. The Jews, therefore, felt such calamities most severely. In particular, Nini refers to the drought and famine of the 1890s, and subsequently of 1903 which “decimated the population” of San’a.

For most of the period dealt with here, it seems Jews were safer and better off with the tribespeople particularly in the North and North Eastern regions of Yemen, than they were in San’a and the major cities. Yet they were nevertheless subject peoples: clients, and there was therefore a significant power imbalance. Moreover, while fear was a factor motivating their protection, it was also something which could place their lives in great danger even in these very regions where they were otherwise relatively safe, dignified, and well-protected.

Therefore, it cannot be said that relations between Jews and Arabs in Yemen were fine until the establishment of Israel as a modern state. Throughout their long history in Yemen, they went through periods of enormous hardship and suffering. Even in the tribal areas where Jews may have been relatively well-off, their position was precarious and in times of drought and famine, they were at a great disadvantage. Since their position was tied to the need for protection and the goodwill of their neighbours rather than any fundamental human and civil rights, this placed them in a very dependent position, which could change with the ecological or political situation.

Photo from Shalom Seri & Naftali Ben-David (Eds.) A Journey to Yemen and its Jews. 1991. Tel Aviv.

References:

Barer, S. 1952. The Magic Carpet. London, Secker and Warburg. 101.

Bujra, A.S. 1971. Politics of Stratification: A Study of Political Change in a South Arabian Town. Oxford University Press.

“Economic History” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, VI. Keter Publishing House, Jerusalem Ltd. 1972.

Esposito, J.L. 2004. The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. New York.

Eraqi Klorman, Bat-Zion. 2009. “Yemen: Religion, magic, and Jews”, in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 39. 2009. 125-134.

Goitein, S.D. 1964. Jews and Arabs: their contacts through the ages. Schocken Books, New York.

Goitein, S.D. 1947. Tales from the land of Sheba. Schocken Books, New York.

Goitein, S.D. (Ed.) 1941. Travels in Yemen. (English synopsis.) Jerusalem, Hebrew University Press.

Nini, Yehuda. 1991. The Jews of Yemen 1800 – 1914. Harwood Academic Publishers, Oxford, Zurich.

Rodinson, M. 1977. Mohammed. (Translated: A. Carter.) Penguin Books, Harmondsworth.

Saphir, Y. 1866. Even Sapir. Jerusalem.

Tobi, Yosef. 1999. The Jews of Yemen. Studies in Their History and Culture. Brill. Leiden, Boston, Köln.

I was living in Israel during 1990/91 at the time when, just after Perestroika, Jews from the Soviet Union, finally free to leave, were flooding into Israel. I studied Hebrew in an Ulpan (language school) where most of the other students were from the former Soviet Union (mainly Russia and the Ukraine, but also Georgia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan). When we had a tea break, these students would form a massive queue and each take as many biscuits as they could possibly hold, not caring whether those furthe

I was living in Israel during 1990/91 at the time when, just after Perestroika, Jews from the Soviet Union, finally free to leave, were flooding into Israel. I studied Hebrew in an Ulpan (language school) where most of the other students were from the former Soviet Union (mainly Russia and the Ukraine, but also Georgia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan). When we had a tea break, these students would form a massive queue and each take as many biscuits as they could possibly hold, not caring whether those furthe

I actually think this is Mac’s brother. If Mac’s brother sees this, maybe he’ll confirm?

I actually think this is Mac’s brother. If Mac’s brother sees this, maybe he’ll confirm?

My first love from early childhood was music: classical piano-playing, and singing (especially folk), accompanying myself on my beloved guitar.

My first love from early childhood was music: classical piano-playing, and singing (especially folk), accompanying myself on my beloved guitar.